The histories of Patagonia, Sonoita and Elgin are as colorful as their sunsets and as rich as the ore that came from local mines. Native Americans, Spaniards, Mexicans, ranchers, miners, and Jesuit priests have all inhabited this land over the past five hundred years, and recent archeological work suggests evidence of human activity by hunting and gathering cultures of the Archaic period (7000-1 B.C.).

Patagonia Geography

Patagonia nestles in the Sky Islands at an elevation of 4,050 feet and has a population of approximately 900. This unique mountain town is 18 miles north of the U.S./Mexico border and one hour’s drive south of the Tucson International Airport. The surrounding Coronado National Forest provides Patagonia with a sense of seclusion, yet proximity to a major airport.

Patagonia lies in a narrow valley between the Santa Rita Mountains, which peak at 9,453 feet and and the Patagonia Mountains, which peak at 7,221 feet, at the intersection of Harshaw Creek and Sonoita Creek. Accordingly, the riparian habitat created by the confluence of these creeks provided ideal conditions for clusters of ancient settlements with ruins and petroglyphs of the Anasazi leaving their mark.

The San Rafael Valley is located east of Patagonia. It is pristine high desert grassland with very low population and grand vistas. A loop drive can be made from Patagonia to the valley and back by taking Harshaw Creek Road to FR 58. Follow FR 58 to San Rafael Road and head south to the charming old border town of Lochiel. Take Duquesne Road (FR 61) west from Lochiel. Be sure to keep an eye open for the monument to Fray Marcos de Niza, the first European to enter in to what is now the US from Mexico. The monument is located on the south side of Duquesne Road as you are leaving Lochiel. Moving along on Duquesne Road you will pass the ghost towns of Duquesne and Washington Camp. The roads are all gravel and very well maintained. The trip can take a couple hours or all day, depending on stops. Be sure to take plenty of food and water since the valley has no services.

History — Native Americans and Spanish Missions

The area’s original inhabitants were Native Americans who found that the lush area along the Sonoita and Harshaw Creeks provided ideal living conditions with plentiful hunting and fishing opportunities. In 1539, Spanish explorer Fray Marcos de Niza entered the area near present-day Lochiel on the Mexican border. A century and a half later, the Jesuit priest Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino traveled through the region, establishing missions and mapping the territory.

Spanish records indicate that in 1698 Father Eusebio Francisco Kino encouraged his group to leave the San Pedro River and make their way up to Sonoita Creek. There they encountered clusters of indigenous people living along Sonoita Creek in Patagonia, and in 1701, Kino designated Sonoita as one of his visitas (overnight houses located between full-fledged missions). The area then became part of the Mission at Guevavi.

Cattle ranching, mining and the railroads have come and gone, leaving Patagonia as a hybrid borderland culture with a population that is over half of Hispanic origin, consisting of shopkeepers, wellness enthusiasts and practitioners, artists, craftspersons, farmers, former cowboys, vaqueros, miners and retirees.

Gadsden Purchase Invites Prospecting and Land Use

1851 saw the historic visitation of U.S. Boundary Commissioner John R. Bartlett, who was one of the first to publish descriptions of the Sonoita Valley. He designated it too dangerous and impassible for inhabitants, and suggested the U.S. boundary lie farther north. But by 1853, the Gadsden Purchase made the southeastern corner of Arizona, then the northern part of Mexico, part of the United States. The vast Spanish land grants began to break up as Easterners moved west to homestead and ranch.

In the late 1850s, prospectors mined the silver-rich mountains east of Sonoita and the boom was on. The Patagonia Mountains were filled with rich ore bodies, and by the 1860s, the mining industry procured vast amounts of silver and lead each year. The growth of mining towns such as Mowry, Harshaw, Washington Camp, and Duquesne reflect the extent of the mining boom that last until the early part of the 20th century.

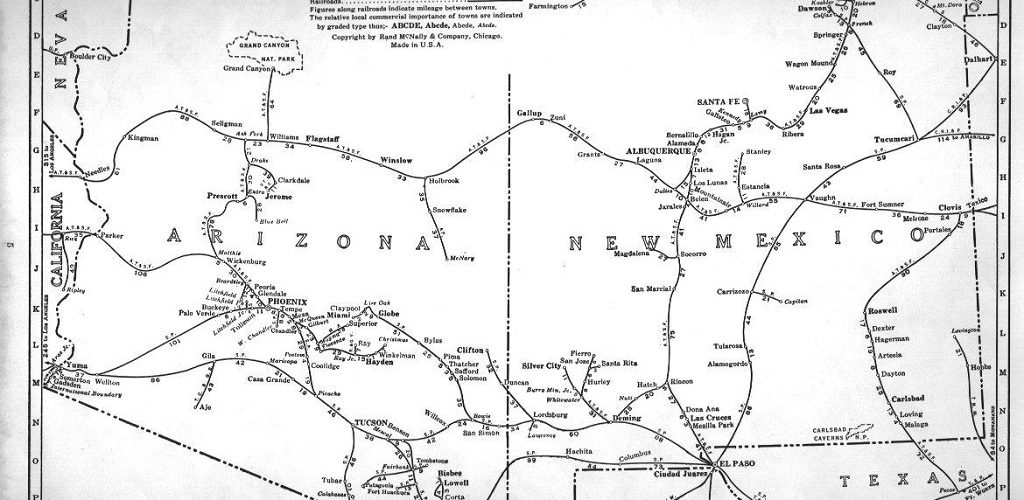

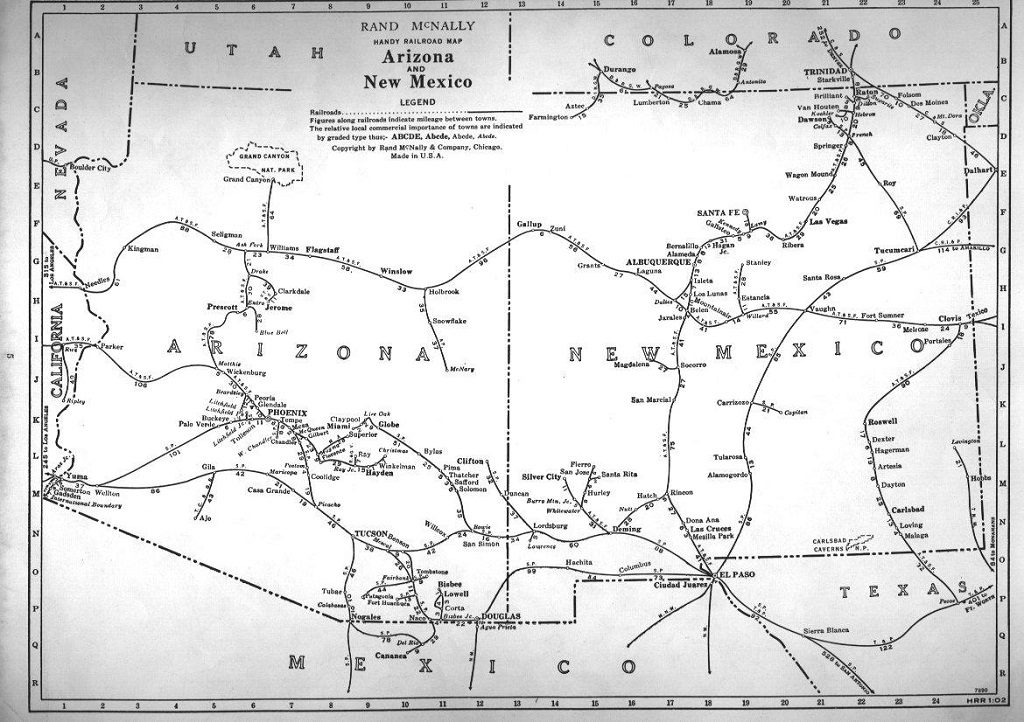

Railroads Connect Miners and Attract Ranchers

The Mountain Empire got a big boost when the New Mexico & Arizona Railroad connected the area to Mexico in 1882. The villages of Sonoita (known then as the Sonoita Settlement) and Elgin came into being with the arrival of the Benson-to-Nogales Railway, which at one point had three daily stops in Patagonia. Despite serious conflicts with Apaches, prospectors headed west to mine silver, gold, lead, copper, and other minerals. Ranchers thrived in Sonoita’s rich grasslands and the railroads allowed as many as 3,000 head of cattle a day to be shipped to the East.

The End of an Era

A direct rail line from Tucson to Nogales, Sonora, as well as the decline in mining activity, cattle shipping, and population caused segments of the New Mexico & Arizona Railroad to be abandoned between 1926 and 1962. In July 1929, after the tracks were washed out near Patagonia, the bridges were salvaged and the rails picked up between Flux Siding and Patagonia (about four miles of track).

The last ore was shipped to the smelter in 1960, and the last of the original railroad line was removed in 1962. A Patagonia resident bought the depot in 1964 to save it from being demolished. A year later he sold it to the local Rotary Club who began the long process of restoring it. The Patagonia Station grounds were donated to the Town of Patagonia and made into a Town Park in 1966. The restored depot has housed the town’s municipal offices since 1974.

Cattle ranches, no longer the vast spreads of the early days, still remain a vital part of the economy and culture. Fourth and fifth generation ranchers and miners still live in the area, as do newcomers such as artists and retirees. Residents have restored historic buildings, and many are in use today….constant reminders of the boom years of yesterday.

The bustle of mining may be long gone, but the memories of this once-prominent industry still linger in the wilderness of Southern Arizona. Today, the mining camp ghost towns of Mowry, Harshaw, Washington Camp, and Duquesne bear mute testimony to the boom days of yesteryear.

Just 20-45 minutes east and southeast of Patagonia you’ll find remnants of towns that once numbered in the thousands. Some buildings still stand and several cemeteries mark the passing of the town folk that lived the hard life of the pioneer days. Note: Some of these buildings stand on what is now private property. Please heed all “No Trespassing” signs.

The Patagonia area also boasts two very interesting cemeteries. The Patagonia Cemetery is located at the top of a steep hill at the southwest end of town. Look for the American Flag flying at the top of the hill and a very steep climb up a road on the left. The Harshaw Cemetery is located in the ghost town of Harshaw, located about 15 minutes east of town (visit www.ghosttowns.com for a map). Once you get there, look for a small iron gate on the side of the ridge on the west side of the road. A good landmark is the very large sycamore tree just south of the cemetery on the west side of the road.